Programming Language Pragmatics 第一章笔记下

An Overview of Compilation

Compilers are among the most well-studied classes of computer programs. We will consider them repeatedly throughout the rest of the book, and in Chapters 2, 4, 14, and 16 in particular. The remainder of this section provides an introductory overview.

编译器是最受人研究的计算机程序类别之一。我们将在本书的其余部分多次考虑它们,特别是在第2、4、14和16章。本节的其余部分提供了一个简要概述。

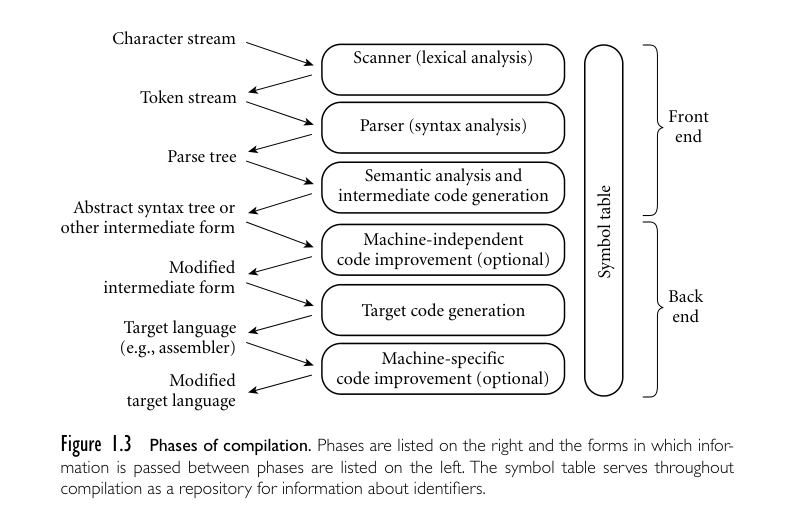

In a typical compiler, compilation proceeds through a series of well-defined phases, shown in Figure 1.3. Each phase discovers information of use to later phases, or transforms the program into a form that is more useful to the subsequent phase.

在典型的编译器中,编译过程经过一系列明确定义的阶段,如图1.3所示。每个阶段都会发现对后续阶段有用的信息,或将程序转换为对后续阶段更有用的形式。

The first few phases (up through semantic analysis) serve to figure out the meaning of the source program. They are sometimes called the front end of the compiler. The last few phases serve to construct an equivalent target program. They are sometimes called the back end of the compiler. Many compiler phases can be created automatically from a formal description of the source and/or target languages.

前几个阶段(直到语义分析)用于弄清源程序的含义。它们有时被称为编译器的前端。最后几个阶段用于构建一个等价的目标程序。它们有时被称为编译器的后端。许多编译器阶段可以根据源语言和/或目标语言的形式化描述自动生成。

One will sometimes hear compilation described as a series of passes. A pass is a phase or set of phases that is serialized with respect to the rest of compilation: it does not start until previous phases have completed, and it finishes before any subsequent phases start. If desired, a pass may be written as a separate program, reading its input from a file and writing its output to a file. Compilers are commonly divided into passes so that the front end may be shared by compilers for more than one machine (target language), and so that the back end may be shared by compilers for more than one source language. In some implementations the front end and the back end may be separated by a“middle end”that is responsible for language- and machine-independent code improvement. Prior to the dramatic increases in memory sizes of the mid to late 1980s, compilers were also sometimes divided into passes to minimize memory usage: as each pass completed, the next could reuse its code space.

有时会听到将编译描述为一系列传递。传递是一个相对于编译的其余部分进行串行化的阶段或一组阶段:它在前一阶段完成之前不会开始,并且在任何后续阶段开始之前就会结束。如果需要,可以将传递编写为一个独立的程序,从文件读取输入并将输出写入文件。编译器通常被划分为传递,以便前端可以被多台机器(目标语言)的编译器共享,后端可以被多种源语言的编译器共享。在一些实现中,前端和后端可能被一个负责语言和机器无关代码改进的“中端”分开。在20世纪80年代中期到晚期内存大小大幅增加之前,有时也将编译器划分为传递以最小化内存使用:当每个传递完成时,下一个传递可以重用其代码空间。

Lexical and Syntax Analysis

Scanning is also known as lexical analysis. The principal purpose of the scanner is to simplify the task of the parser, by reducing the size of the input (there are many more characters than tokens) and by removing extraneous characters like white space. The scanner also typically removes comments and tags tokens with line and column numbers, to make it easier to generate good diagnostics in later phases. One could design a parser to take characters instead of tokens as inputdispensing with the scanner—but the result would be awkward and slow.

扫描也被称为词法分析。扫描器的主要目的是简化解析器的任务,通过减少输入的大小(字符比标记要多得多),并删除多余的字符,如空白。扫描器通常还会移除注释,并为标记添加行号和列号,以便在后续阶段更容易生成良好的诊断信息。理论上可以设计一个解析器,接受字符而不是标记作为输入,从而省去扫描器,但结果会很笨拙且效率低下。

Parsing organizes tokens into a parse tree that represents higher-level constructs (statements, expressions, subroutines, and so on) in terms of their constituents. Each construct is a node in the tree; its constituents are its children. The root ofthe tree is simply “program”; the leaves, from left to right, are the tokens received from the scanner. Taken as a whole, the tree shows how the tokens fit together to make a valid program. The structure relies on a set of potentially recursive rules known as a context-free grammar. Each rule has an arrow sign (−→) with the construct name on the left and a possible expansion on the right. In C, for example, a while loop consists of the keyword while followed by a parenthesized Boolean expression and a statement:

解析将标记组织成一个解析树,该树以其组成部分表示高级构造(语句、表达式、子程序等)。每个构造都是树中的一个节点;它的组成部分是它的子节点。树的根节点简单地是“程序”;从左到右的叶子节点是来自扫描器的标记。整体上看,树显示了标记如何组合在一起形成一个有效的程序。该结构依赖于一组潜在递归的规则,称为无上下文语法。每个规则都有一个箭头符号(→),左边是构造名称,右边是可能的扩展。例如,在C语言中,while循环由关键字while后跟括号中的布尔表达式和一个语句组成:

iteration-statement −→ while ( expression ) statement

The statement, in turn, is often a list enclosed in braces:

statement −→ compound-statement

compound-statement −→ { block-item-list opt }

where

block-item-list opt −→ block-item-list

or

block-item-list opt −→ ϵ

and

block-item-list −→ block-item

block-item-list −→ block-item-list block-item

block-item −→ declaration

block-item −→ statement

Here ϵ represents the empty string; it indicates that block-item-list opt can simply be deleted. Many more grammar rules are needed, of course, to explain the full structure of a program.

这里的 ϵ 代表空字符串;它表示 block-item-list opt 可以被简单地删除。当然,需要更多的语法规则来解释程序的完整结构。

A context-free grammar is said to define the syntax of the language; parsing is therefore known as syntax analysis. There are many possible grammars for C (an infinite number, in fact); the fragment shown above is taken from the sample grammar contained in the official language definition [Int99]. A full parse tree for our GCD program (based on a full grammar not shown here) appears in Figure 1.4. While the size of the tree may seem daunting, its details aren’t particularly important at this point in the text. What is important is that (1) each individual branching point represents the application of a single grammar rule, and (2) the resulting complexity is more a reflection of the grammar than it is of the input program. Much of it stems from (a) the use of such artificial “constructs” as block item-list and block item-list opt to generate lists of arbitrary length, and (b) the use of the equally artificial assignment-expression, additive expression, multiplicative-expression, and so on, to capture precedence and associativity in arithmetic expressions. We shall see in the following subsection that much of this complexity can be discarded once parsing is complete.

一个无上下文语法被认为定义了语言的语法;因此,解析也被称为语法分析。对于C语言有许多可能的语法(实际上是无限多个);上面显示的片段取自官方语言定义中包含的样例语法[Int99]。基于未在此处显示的完整语法的我们的GCD程序的完整解析树显示在图1.4中。虽然树的大小可能看起来令人生畏,但在本文的这一阶段,其细节并不特别重要。重要的是:(1)每个单独的分支点代表一个单一的语法规则的应用,以及(2)产生的复杂性更多地反映了语法而不是输入程序本身。其中许多复杂性源自于(a)使用诸如 block item-list 和 block item-list opt 之类的人为“构造”来生成任意长度的列表,以及(b)使用同样人为的 assignment-expression、additive-expression、multiplicative-expression 等来捕获算术表达式中的优先级和结合性。在接下来的小节中,我们将看到一旦解析完成,许多这些复杂性都可以被丢弃。

In the process of scanning and parsing, the compiler checks to see that all of the program’s tokens are well formed, and that the sequence of tokens conforms to the syntax defined by the context-free grammar. Any malformed tokens (e.g., 123abc or $@foo in C) should cause the scanner to produce an error message. Any syntactically invalid token sequence (e.g., A = X Y Z in C) should lead to an error message from the parser.

在扫描和解析的过程中,编译器检查程序的所有标记是否格式良好,并且标记序列是否符合上下文无关语法定义的语法。任何格式不良的标记(例如,在C语言中的123abc或$@foo)都应该导致扫描器产生错误消息。任何语法上无效的标记序列(例如,在C语言中的A = X Y Z)应该导致解析器产生错误消息。

Semantic Analysis and Intermediate Code Generation

Semantic analysis is the discovery of meaning in a program. The semantic analysis phase of compilation recognizes when multiple occurrences of the same identifier are meant to refer to the same program entity,and ensures that the uses are consistent. In most languages the semantic analyzer tracks the types of both identifiers and expressions, both to verify consistent usage and to guide the generation of code in later phases.

语义分析是对程序中含义的发现。编译的语义分析阶段识别了相同标识符的多次出现意味着引用同一程序实体,并确保这些用法是一致的。在大多数语言中,语义分析器跟踪标识符和表达式的类型,既用于验证一致的使用,也用于指导后续阶段代码的生成。

To assist in its work,the semantic analyzer typically builds and maintains a symbol table data structure that maps each identifier to the information known about it. Among other things, this information includes the identifier’s type, internal structure (if any), and scope (the portion of the program in which it is valid).

为了辅助其工作,语义分析器通常构建并维护一个符号表数据结构,将每个标识符映射到已知的信息。这些信息包括标识符的类型、内部结构(如果有的话)以及作用域(其有效的程序部分)。

Using the symbol table, the semantic analyzer enforces a large variety of rules that are not captured by the hierarchical structure of the context-free grammar and the parse tree. In C, for example, it checks to make sure that

利用符号表,语义分析��器强制执行许多上下文无关语法和解析树所不能捕获的规则。例如,在C语言中,它会检查确保

- Every identifier is declared before it is used.

- No identifier is used in an inappropriate context (calling an integer as a subroutine, adding a string to an integer, referencing a field of the wrong type of struct, etc.).

- Subroutine calls provide the correct number and types of arguments.

- Labels on the arms of a switch statement are distinct constants.

- Any function with a non-void return type returns a value explicitly.

In many compilers, the work of the semantic analyzer takes the form of semantic action routines,invoked by the parser when it realizes that it has reached a particular point within a grammar rule.

在许多编译器中,语义分析器的工作以语义动作例程的形式进行,当解析器意识到已经到达语法规则中的特定点时,会调用这些例程。

Of course, not all semantic rules can be checked at compile time. Those that can are referred to as the static semantics of the language. Those that must be checked at run time are referred to as the dynamic semantics of the language. C has very little in the way of dynamic checks (its designers opted for performance over safety). Examples of rules that other languages enforce at run time include the following.

当然,并非所有的语义规则都能在编译时进行检查。那些可以在编译时检查的规则被称为语言的静态语义。那些必须在运行时检查的规则被称为语言的动态语义。C语言在动态检查方面几乎没有什么(其设计者选择了性能而不是安全性)。其他语言在运行时执行的规则的例子包括以下内容。

- Variables are never used in an expression unless they have been given a value.

- Pointers are never dereferenced unless they refer to a valid object.

- Array subscript expressions lie within the bounds of the array.

- Arithmetic operations do not overflow.

When it cannot enforce rules statically, a compiler will often produce code to perform appropriate checks at run time, aborting the program or generating an exception if one of the checks then fails. (Exceptions will be discussed in Section 8.5.) Some rules, unfortunately, may be unacceptably expensive or impossible to enforce, and the language implementation may simply fail to check them. In Ada, a program that breaks such a rule is said to be erroneous; in C its behavior is said to be undefined.

当编译器无法静态地强制执行规则时,通常会生成代码,在运行时执行适当的检查,如果其中一个检查失败,则中止程序或生成异常(异常将在第8.5节中讨论)。遗憾的是,一些规则可能成本过高或无法实施,语言实现可能会简单地不对其进行检查。在Ada中,违反此类规则的程序被称为错误的;在C中,其行为被称为未定义。

A parse tree is sometimes known as a concrete syntax tree, because it demonstrates, completely and concretely, how a particular sequence of tokens can be derived under the rules of the context-free grammar. Once we know that a token sequence is valid, however, much of the information in the parse tree is irrelevant to further phases of compilation. In the process of checking static semantic rules, the semantic analyzer typically transforms the parse tree into an abstract syntax tree (otherwise known as an AST,or simply a syntax tree) by removing most of the “artificial” nodes in the tree’s interior. The semantic analyzer also annotates the remaining nodes with useful information,such as pointers from identifiers to their symbol table entries. The annotations attached to a particular node are known as its attributes. A syntax tree for our GCD program is shown in Figure 1.5.

解析树有时被称为具体语法树,因为它完全而具体地展示了在上下文无关文法规则下特定标记序列的推导过程。然而,一旦我们知道一个标记序列是有效的,解析树中的大部分信息对于编译的后续阶段来说就变得无关紧要了。在检查静态语义规则的过程中,语义分析器通常会通过移除树中大部分“人为”节点,将解析树转换成抽象语法树(又称AST,或者简称语法树)。语义分析器还会为剩余的节点添加有用的信息,比如从标识符到它们的符号表条目的指针。附加到特定节点的注释被称为它的属性。我们的最大公约数程序的语法树如图1.5所示。

In many compilers,the annotated syntax tree constitutes the intermediate form that is passed from the front end to the back end. In other compilers, semantic analysis ends with a traversal of the tree that generates some other intermediate form. One common such form consists of a control flow graph whose nodes resemble fragments of assembly language for a simple idealized machine. We will consider this option further in Chapter 14, where a control flow graph for our GCD program appears in Figure 14.3. In a suite of related compilers, the front ends for several languages and the back ends for several machines would share a common intermediate form.

在许多编译器中,带注释的语法树构成了从前端传递到后端的中间形式。在其他编译器中,语义分析以遍历生成某些其他中间形式的树而结束。一种常见的这种形式包括一个控制流图,其节点类似于简化理想机器的汇编语言片段。我们将在第14章进一步探讨这个选项,在那里我们的GCD程序的控制流图出现在图14.3中。在一套相关的编译器中,多种语言的前端和多种机器的后端将共享一个通用的中间形式。

Target Code Generation

The code generation phase of a compiler translates the intermediate form into the target language. Given the information contained in the syntax tree, generating correct code is usually not a difficult task (generating good code is harder, as we shall see in Section 1.6.4). To generate assembly or machine language, the code generator traverses the symbol table to assign locations to variables, and then traverses the intermediate representation of the program, generating loads and stores for variable references,interspersed with appropriate arithmetic operations, tests, and branches. Naive code for our GCD example appears in Figure 1.6, in x86 assembly language. It was generated automatically by a simple pedagogical compiler.

编译器的代码生成阶段将中间形式转换为目标语言。根据语法树中包含的信息,生成正确的代码通常并不是一项困难的任务(生成优秀的代码更难,正如我们将在1.6.4节中看到的那样)。为了生成汇编或机器语言,代码生成器遍历符号表以为变量分配位置,然后遍历程序的中间表示,生成变量引用的加载和存储,并穿插适当的算术操作、测试和跳转。我们的GCD示例的朴素代码出现在图1.6中,使用x86汇编语言编写。这是由一个简单的教学编译器自动生成的。

The assembly language mnemonics may appear a bit cryptic,but the comments on each line (not generated by the compiler!) should make the correspondence between Figures 1.5 and 1.6 generally apparent. A few hints: esp, ebp, eax, ebx, and edi are registers (special storage locations, limited in number, that can be accessed very quickly). -8(%ebp) refers to the memory location 8 bytes before the location whose address is in register ebp; in this program, ebp serves as a base from which we can find variables i and j. The argument to a subroutine call instruction is passed by pushing it onto a stack, for which esp is the top-of-stack pointer. The return value comes back in register eax. Arithmetic operations overwrite their second argument with the result of the operation.

这些汇编语言助记符可能看起来有点晦涩,但每行的注释(并非由编译器生成!)应该能够使图1.5和图1.6之间的对应关系基本上显而易见。一些提示:esp、ebp、eax、ebx和edi是寄存器(特殊的存储位置,数量有限,可以被非常快速地访问)。-8(%ebp)指的是在寄存器ebp中存储地址的位置的前8个字节的内存位置;在这个程序中,ebp用作基址,我们可以从中找到变量i和j。对于子程序调用指令,参数是通过将其推送到堆栈中传递的,esp是堆栈顶部指针。返回值存放在寄存器eax中。算术操作会用操作的结果覆盖其第二个参数。

Often a code generator will save the symbol table for later use by a symbolic debugger, by including it in a nonexecutable part of the target code.

通常,代码生成器会将符号表保存下来,以便将来被符号调试器使用,方法是将其包含在目标代码的不可执行部分中。

Code Improvement

Code improvement is often referred to as optimization, though it seldom makes anything optimal in any absolute sense. It is an optional phase of compilation whose goal is to transform a program into a new version that computes the same result more efficiently—more quickly or using less memory, or both.

代码改进通常被称为优化,尽管在任何绝对意义上它很少使任何东西都变得最佳。它是编译的一个可选阶段,其目标是将程序转换为一个计算相同结果的更高效版本——更快或者使用更少的内存,或者两者兼而有之。

Some improvements are machine independent. These can be performed as transformations onthe intermediate form. Other improvements require an understanding of the target machine (or of whatever will execute the program in the target language). These must be performed as transformations on the target program. Thus code improvement often appears as two additional phases of compilation, one immediately after semantic analysis and intermediate code generation, the other immediately after target code generation.

有些改进是与机器无关的。这些可以作为对中间形式的转换来执行。其他改进需要对目标机器(或者在目标语言中执行程序的任何内容)的理解。这些必须作为对目标程序的转换来执行。因此,代码改进通常出现为编译的两个额外阶段,一个紧跟语义分析和中间代码生成之后,另一个紧跟目标代码生成之后。

Applying a good code improver to the code in Figure 1.6 produces the code shown in Example 1.2 (page 5). Comparing the two programs, we can see that the improved version is quite a lot shorter. Conspicuously absent are most of the loads and stores. The machine-independent code improver is able to verify that i and j can be kept in registers throughout the execution of the main loop. (This would not have been the case if,for example,the loop contained a call to a subroutine that might reuse those registers, or that might try to modify i or j.) The machine specific code improver is then able to assign i and j to actual registers of the target machine. For modern microprocessor architectures, particularly those with so-called superscalar implementations (ones in which separate functional units can execute instructions simultaneously), compilers can usually generate better code than can human assembly language programmers.

将图1.6中的代码应用于良好的代码改进器会产生示例1.2(第5页)中所示的代码。比较这两个程序,我们可以看到改进后的版本要短得多。明显缺失的是大部分的加载和存储操作。机器无关的代码改进器能够验证在主循环的执行过程中,i和j可以一直保持在寄存器中。(如果,例如,循环中包含对子程序的调用,该子程序可能会重用这些寄存器,或者可能试图修改i或j,那么情况就不同了。)然后,特定于机器的代码改进器能够将i和j分配给目标机器的实际寄存器。对于现代微处理器架构,特别是那些具有所谓的超标量实现(可以同时执行指令的独立功能单元),编译器通常能够生成比人类汇编语言程序员更好的代码。

Summary and Concluding Remarks

In this chapter we introduced the study of programming language design and implementation. We considered why there are so many languages, what makes them successful or unsuccessful, how they may be categorized for study, and what benefits the reader is likely to gain from that study. We noted that language design and language implementation are intimately related to one another. Obviously an implementation must conform to the rules of the language. At the same time, a language designer must consider how easy or difficult it will be to implement various features, and what sort of performance is likely to result for programs that use those features.

在本章中,我们介绍了编程语言设计和实现的研究。我们考虑了为什么会有这么多种语言,是什么让它们成功或失败,它们可以如何分类进�行研究,以及读者可能从这些研究中获得什么好处。我们指出语言设计和语言实现之间密切相关。显然,实现必须符合语言的规则。同时,语言设计者必须考虑实现各种特性的难易程度,以及使用这些特性的程序可能会产生怎样的性能。

Language implementations are commonly differentiated into those based on interpretation and those based on compilation. We noted, however, that the difference between these approaches is fuzzy,and that most implementations include a bit of each. As a general rule, we say that a language is compiled if execution is preceded by a translation step that (1) fully analyzes both the structure (syntax) and meaning (semantics) of the program, and (2) produces an equivalent program in a significantly different form. The bulk of the implementation material in this book pertains to compilation.

编程语言的实现通常分为基于解释和基于编译的两种类型。然而,我们指出这两种方法之间的区别是模糊的,并且大多数实现都包含了两者的一些特点。一般而言,我们说一种语言是编译型的,如果在执行之前需要经过一个翻译步骤,这个步骤会(1)完全分析程序的结构(语法)和含义(语义),以及(2)生成一个在形式上明显不同的等效程序。本书中大部分的实现内容涉及编译。

Compilers are generally structured as a series of phases. The first few phases scanning, parsing, and semantic analysis—serve to analyze the source program. Collectively these phases are known as the compiler’s front end. The final few phases—intermediate code generation, code improvement, and target code generation—are known as the back end. They serve to build a target program preferably a fast one—whose semantics match those of the source.

编译器通常被构建为一系列阶段。最初的几个阶段——扫描、解析和语��义分析——用于分析源程序。这些阶段统称为编译器的前端。最后的几个阶段——中间代码生成、代码优化和目标代码生成——被称为后端。它们用于构建目标程序——最好是一个语义与源程序相匹配且快速的程序。

Chapters 3,6,7,8,and 9 form the core of the rest of this book. They cover fundamental issues of language design, both from the point of view of the programmer and from the point of view of the language implementor. To support the discussion of implementations, Chapters 2 and 4 describe compiler front ends in more detail than has been possible in this introduction. Chapter 5 provides an overview of assembly-level architecture. Chapters 14 through 16 discuss compiler back ends, including assemblers and linkers, run-time systems, and code improvement techniques. Additional language paradigms are covered in Chapters 10 through 13. Appendix A lists the principal programming languages mentioned in the text, together with a genealogical chart and bibliographic references. Appendix B contains a list of “Design & Implementation” sidebars; Appendix C contains a list of numbered examples.

第3、6、7、8和9章构成了本书的核心部分。它们涵盖了语言设计的基本问题,既从程序员的角度,也从语言实现者的角度进行了讨论。为了支持对实现的讨论,第2章和第4章比本介绍部分更详细地描述了编译器的前端。第5章概述了汇编级架构。第14至16章讨论了编译器的后端,包括汇编器和链接器、运行时系统以及代码优化技术。第10至13章涵盖了额外的语言范式。附录A列出了文本中提到的主要编程语言,以及它们的谱系图和参考文献。附录B包含了“设计与实现”方块的列表;附录C包含了编号示例的列表。